The Tang Dynasty (618-907), covering a period of 289 years, was not long in relation to China’s 5,000-year civilization. It is nonetheless considered to be the greatest dynasty of ancient China. During its zenith of 140 years (618-765), the Tang Dynasty not only ushered into China a period of unprecedented development and prosperity but also contributed to the development and progress of humankind as a whole.

The Chinese people are particularly proud of their two most resplendent dynastic periods — the Han and the Tang — and consider them to be symbolic of China and the Chinese nation. Countless Chinese people, whether living in China or overseas, still refer to themselves as “Hanren” (Han person/people) or “Tangren” (Tang person/people). In European and American countries, the numerous Chinese communities, or “China Towns,” are known as “Tangren Jie,” meaning the neighborhood or street inhabited by the Tang people.

Introduction

Faced with disastrous military setbacks in Korea and revolt on the streets, Yangdi was assassinated by one of his high officials. Meanwhile, another Sui official, posted in the border garrison of Taiyuan, turned his troops back on the capital. His name was Li Yuan (known posthumously as Gaozu), and he was to establish the Tang Dynasty (618-907), commonly regarded by the Chinese as the most glorious period in their history.

Gaozu’s grab at dynastic succession was not without contest, and it was to take 10 years before the last of his rivals was defeated. Once this was achieved, however, the Tang set about putting the house in order. A pyramidal administration was established, with the emperor at its head, two policy-formulating ministries, and a Department of State Affairs below this, followed in turn by nine courts and six boards dealing with specific administrative areas. In a move to discourage the development of regional power bases, the empire was divided into 300 perfect-I lures (zhou) and 1500 counties (xian), a regional breakdown that persists to this day.

Also Read

The accession of Gaozu’s son, Taizong (600-649), to the imperial throne saw a continuation of the early Tang’s successes. He was one of the greatest emperors in China’s history and virtually the creator of the Tang Dynasty. Military conquests re-established Chinese control of the silk routes and contributed to an influx of traders, producing an unprecedented ‘internationalization’ of Chinese society.

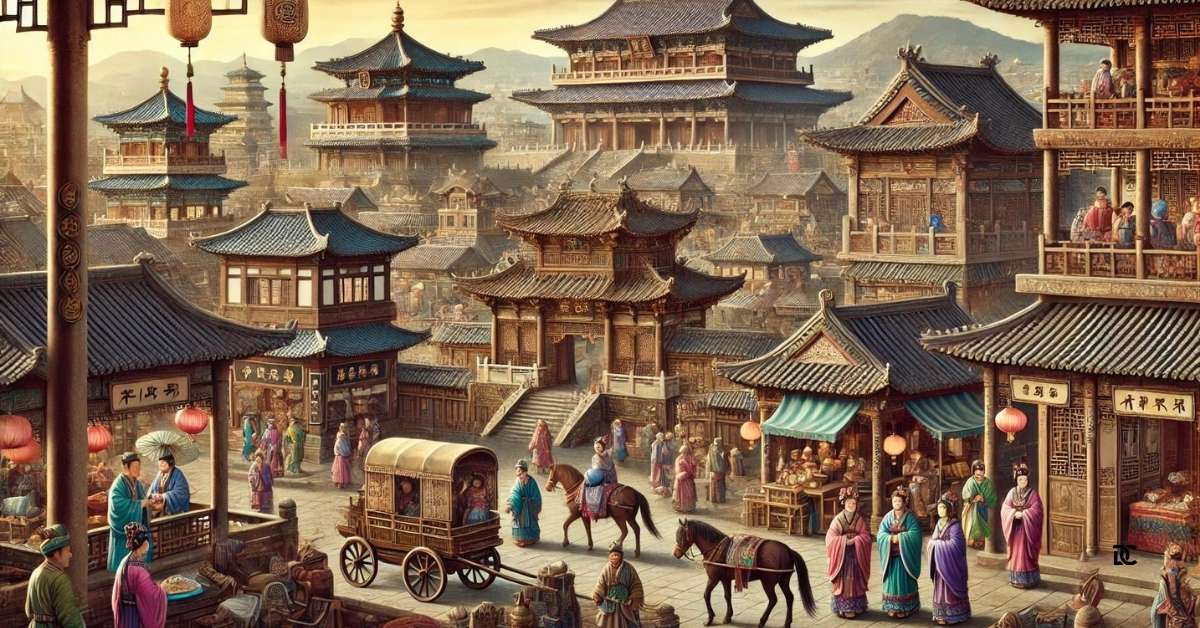

The major cities of Chang’an, Luoyang, and Guangzhou (formerly Canton), as well as many other trading centers, were all home to foreign communities. Mainly from Central Asia, these communities brought with them new religions, food, music, and artistic traditions. Later, during the Tang Dynasty, foreign contact was extended to Persia, India, Malaysia, Indonesia, and Japan. By the 9th century, the city of Guangzhou was estimated to have a foreign population of 100,000.

Buddhism also flourished under the Tang. Chinese pilgrims, notably the famous wanderer Xuan Zang, who was the most famous traveler and translator of Buddhist scriptures in the Tang Dynasty, made their way to India, bringing back with them Buddhist scriptures that, in turn, brought about a Buddhist renewal. Translation, which until this time had expensively sini-sized difficult Buddhist concepts, was undertaken with new rigor, and Chinese Buddhist texts increased vastly in number. One of the consequences of this, however, was a schism in the Buddhist faith.

In reaction to the complexity of many Buddhist texts being translated from Sanskrit, the Chan School (more famously known by its Japanese name, Zen or Nokori) arose. Chan looked to bypass the complexities of scriptural study through discipline and meditation, while another Buddhist phenomenon, the Pure Land School (later to become the most important form of Chinese Buddhism), concerned itself with attaining the ‘Western Paradise.’

For the Chinese, the apex of Tang Dynastic glory was the reign of Xuanzong (685 – 761 ), known also by the title Minghuang, or the ‘Radiant Emperor’. His capital, Chang’an, was one of the greatest cities in the world, with a population of over one million. His court was a magnet to scholars and artists throughout the country and home for a time to poets such as Du Fu and Li Bai, perhaps China’s two most famous rhymers. His reign similarly saw a flourishing of the arts, dance, and music, as well as a remarkable religious diversity.

Some might say that all this artistic activity was an indication that the empire was beginning to go a bit soft at the core. Xuanzong’s increasing preoccupation with the arts, Tantric Buddhism, Taoism, one of his consorts, Yang Guifei, and whatever else captured his fancy meant that the affairs of the state were largely left to his administrators.

A Lushan, a general in the northeast, took this opportunity to build up a huge power base in the region, and before long (755), he made his move on the rest of China. He led the rebellion and took Chang’an. Emperor Xuan Zong fled in panic towards Sichuan. The fighting, which dragged on for nearly 10 years, overran the capital and caused massive dislocations of people and millions of deaths. Although Tang forces regained control of the empire, it was the beginning of the end for the Tang.

Tang power gradually weakened during the 8th and 9th centuries. In the northwest, Tibetan warriors overran Tang garrisons, while to the south, the Nanzhao kingdom centered in Dali, Yunnan, posed a serious threat to Sichuan. Meanwhile, in the Chinese heartland of the Yangzi region and Zhejiang, heavy taxes and a series of calamities engendered wide-ranging discontent that culminated in Huang Cao, the head of a loose grouping of bandit groups, ransacking the capital.

From 907 to 959, until the establishement of the Song Dynasty, China was once again racked by wars between contenders for the mandate of heaven. It is a period often referred to as the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms Period.

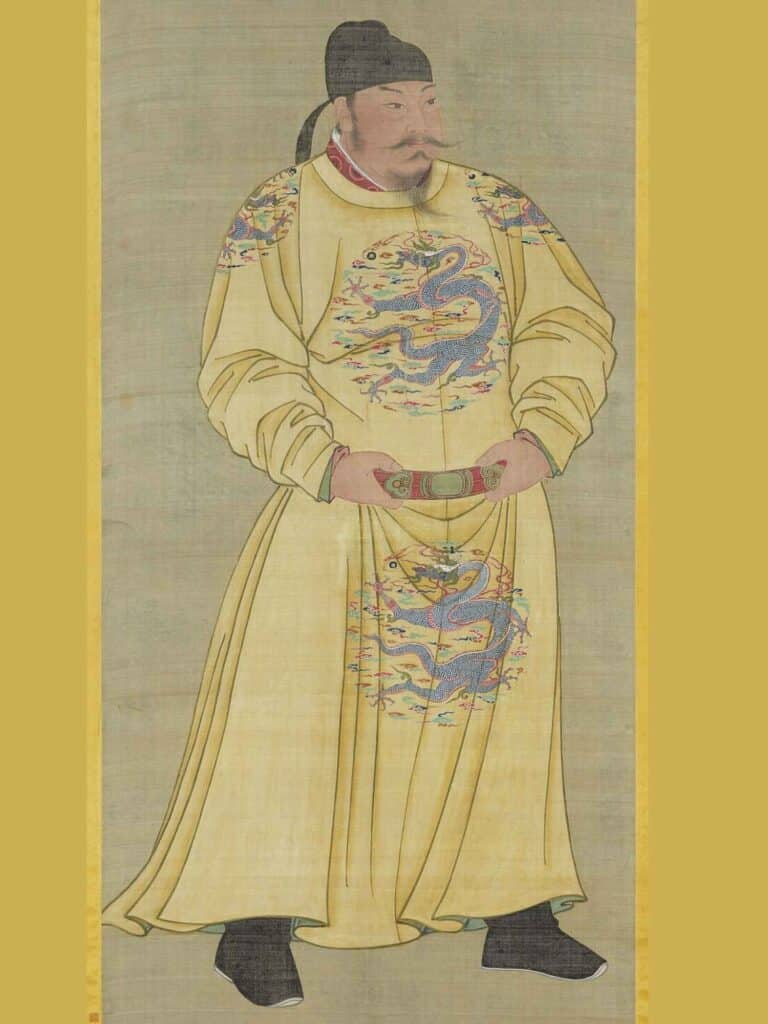

Li Shimin: A Peerless Emperor

For thousands of years prior to the downfall of the last emperor of the Qing Dynasty in 1911, the rulers of slave and feudal societies in China had exercised absolute autocracy, wherein a single person had supreme power over the law and the nation. This supreme figure was thus the arbiter of the course of the historical development and, therefore, the fate of the country, as well as the well-being of its population. For thousands of years, ruthless and tyrannical rulers inflicted misery and disaster upon the Chinese nation, and one who was competent and humane was both longed for and cherished by the ordinary people as an embodiment of their hope for the future.

Li Shimin, a preeminent emperor in Chinese history, was born in 598. His father and grandfather had both been high-ranking officials during the Sui Dynasty (581-618). Li’s childhood was during a period of turmoil. In 605, when Li was 7, Yang Guang, the second emperor of the Sui Dynasty, ascended the throne. This emperor soon became notorious for his debauched lifestyle and cruelty. He squandered the state treasury on lavish imperial buildings, and forced countless people into corvee labor, all of which eventually led to a peasant uprising in 611.

This uprising signaled rebellion and mutiny throughout China. Li Shimin consequently grew up amidst political turbulence and clique intrigue. In 615, at the age of 17, he urged his father, Li Yuan, then a military commander stationed in Taiyuan, to go with the flow of this historic climax and rise against the Sui emperor. Three years later, Li Yuan became the first emperor of the Tang Dynasty.

Stability and solidarity were the top priorities of this new dynasty, and Li Shimin was obviously endowed with both military and political ingenuity. In the course of helping his father stabilize the nation Li Shimin established a strong military force, as well as a large think-tank of expertise in different fields. In 626, at the age of 28, he succeeded his father as emperor.

Li changed the title of his reign to Zhenguan and retained the throne for 23 years. He brought about a new era that laid the foundations for the great prosperity, development, and progress with which the Tang Dynasty became associated in later years. The period of his rule, known as the “Zhenguan Governance,” is acknowledged as a milestone in Chinese history. This reign has rich connotations, being regarded by historians and politicians alike as the model for successful government, while to ordinary people, it is synonymous with a happy life.

An Unsinkable “Boat”

China had been a feudal society for more than 1,000 years prior to Li Shimin’s ascent to the throne. There was, therefore, a sizable accumulation of experience in state administration that had been valued by monarchs of the dynasties preceding the Tang. Li Shimin was also highly appreciative of this wisdom gained from past experience, but the “Zhenguan Governance” of his creation was imbued with an excellence that set it apart from previous governments.

The most important difference in Li Shimin’s approach was that he did not regard the emperor as the “son of God,” believing that the stability of an imperial rule was dependent upon the support of the masses. He said, “The monarch is a boat, and his subjects are the water. Water carries the boat but can also capsize it.” He held that the monarch’s representation of, and care for the interests of, the masses was the essence of governance. His theories were reflected in the daily administration of his reign.

After ascending the throne and remembering well the mistakes that had led to the downfall of the Sui Dynasty, Li Shimin implemented a series of policies that were in the interests of the masses. These included a ban on extravagance, encouragement of frugality, reduction of taxes and corvee labor, construction of water conservancy projects, support of agriculture, and encouragement of a population increase. The emperor did not, however, have heaven’s blessing. During the second year of Zhenguan, China suffered a severe drought, followed by plagues of locusts and subsequent famine. Countless people had no choice but to leave their homes and sell their children. Li Shimin thereupon promulgated a decree whereby children sold could be redeemed by gold and silk issued by the imperial government and returned to their parents. On one occasion, when visiting an area particularly seriously hit by locusts, he picked up a locust and, before eating it, said, “I’d rather it ate my innards.” In the ninth month of that year, he set an example of frugality by dismissing 3,000 maids of honor from the court. The following year, however, China was once more deluged. Li Shimin was seen to have had no power over nature, but his example and identification with the masses were all that the ordinary Chinese could ask for. It is recorded in historical documents: “Due to the dedicated efforts and care on the part of the government, the people had no cause to complain, even though they had to find their food where they could. That year (the fourth year of Zhenguan) yielded an abundant harvest, and those who had fled from famine returned home. A dou (1 decaliter) of rice costs no more than three or four dollars.” In many places, people “did not lock their doors, and when traveling, they took no food with them, instead buying it along the way.”

Li Shimin not only set a good example but was also very strict with local leaders and administrators. He kept a close eye on their performance, making personal inspections and sending people to “supervise local governments, punishing those negligent and promoting the competent, to the great satisfaction of the people.”

A Wise Monarch and Honest Officials

Li Shimin’s wisdom was reflected in dealings with his own staff. Honesty and competence were his top criteria for any official, with no preference based on social or ethnic status. Wei Zheng, the best-known government advisor of the Tang Dynasty, had formerly served Li’s brother, Li Jiancheng, an arch-rival for imperial power. Wei was captured after Li Jiancheng’s defeat and death. Li Shimin was well aware of Wei’s skill as a consultant and asked him why he had advised Li Jiancheng to do away with all dissidents, including Li Shimin himself, thus instigating enmity between the two brothers. Wei answered that had Li Jiancheng followed his advice, he would not have been defeated. Li Shimin appreciated Wei’s talent and honesty and offered him a key governmental position.

Wei was gratified at the emperor’s understanding and trust, and during his time in office, he wrote over 200 reports, giving advice on administration and, at the same time, urging the emperor to solicit opinions from other sources. The emperor was very much in tune with Wei’s concept of a benevolent government and totally agreed with his view that “The monarch is enlightened when he listens to all opinions, and benighted when he is biased,” which has since become a well-known Chinese proverb.

Wei Zheng and Li Shimin did, however, also have their differences. On one occasion, the two quarreled during an imperial audience. On his return to the inner court, the emperor said angrily that Wei Zheng was too willful and that one day he would execute him. The empress congratulated him, saying that it was only when the emperor was wise that his ministers were upright enough to speak their minds. The emperor immediately calmed down.

Li Shimin loved to hunt, but Wei Zheng believed that the emperor should exercise restraint so as not to become obsessed. It is recorded that in the 10th month of the second year of Zhenguan, Li Shimin “wished to go to Nanshan Mountain on a hunting trip, but desisted from telling Wei Zheng for fear he would criticize him. After perching a snipe on his shoulder, he saw Wei Zheng approaching, upon which the emperor hid the bird beneath his robes. Wei talked with the emperor at such length that the bird died.” There were few other emperors who, like Li Shimin, accepted the supervision of their ministers so earnestly.

Li Shimin opened a channel for officials to offer straightforward advice, but also warned them against slandering others, as this would be treated as a crime and severely punished. In 643, Wei Zheng died, and Li Shimin sorely mourned his loss.

At this time of grief, he thus addressed an audience: “Copper can serve as a mirror for us to see that we are properly dressed; the past can serve as a mirror so that we know what is good; and a person can serve as a mirror so that we may know our losses and gains. I have always kept all three of these mirrors, but today, Wei Zheng has died, and one of my mirrors is lost.”

One Family Within the Four Seas

Another area in which Li Shimin excelled was that of dealing with ethnic and foreign affairs. He broke away from conventions of discrimination between the Chinese and the foreign. He stated, “There has since ancient times been a biased belief that the Chinese race is superior, and all others inferior. I love them all as one.” The Tang Dynasty’s economic strength enabled it to open its doors with confidence to foreign people, commodities, ideologies, cultures, and lifestyles. This extensive absorption and integration created a dynasty that was not only of China but also of the whole world.

Ever since his enthronement, Li Shimin had been aware of the great importance of the Silk Road, and during the recovery period of the early Tang Dynasty, launched several military expeditions to restore peace in frontier regions and along the Silk Road. A more congenial environment was thus created for the people of various ethnic groups living on the frontier, and a smooth passage was guaranteed along this Eurasian passageway.

Apart from the Silk Road, seven other overland and marine routes leading to various countries existed during the Tang Dynasty. In the fourth year of Zhenguan, Li Shimin issued a decree allowing merchants to travel and trade freely with frontier inhabitants. He later issued more ordinances with the aim of protecting the safety of merchants and encouraging trade between China and other countries, and also promulgated a series of preferential policies, including the reduction of tariffs and provision of free firewood to travelling merchants.

The Tang Dynasty became the center of world attention for its economic prosperity, material wealth, enlightened politics, social stability, advanced science, and brilliant culture and arts. Huge numbers of foreigners and people of ethnic minorities came to the dynastic capital of Chang’an. A census taken during the third year of Zhenguan showed that the population in Chang’an was one million and included over 100,000 foreigners and people of ethnic minorities. In the fourth year of Zhenguan, the Tujue (Turkic) tribes fragmented, and after Li Shimin’s acceptance of them, hundreds of thousands of Tujue people found shelter under Tang rule. The emperor arranged for all chieftains to become officials in Chang’an and serve in various departments of the imperial government. At this time, the imperial court had over 200 officials, almost half of which were foreigners or from ethnic minorities. Foreign culture, arts, and lifestyles are thus blended into the daily lives of the local people.

During the Tang Dynasty, anything foreign or alien was labeled “hu.” For a time during the Tang Dynasty a “hu” vogue spread throughout China and remained dominant for a lengthy period of time. Like their emperor, the common people of the Tang Dynasty accepted foreigners readily and hospitably, and absorbed the associated accoutrements that they loved or found useful. This integration of things both Chinese and foreign greatly propelled social progress and the development of the Tang Dynasty.

The capital city of Chang’an was a genuine cosmopolis where foreigners were everywhere, from the imperial palace to common streets and alleys and even among the emperor’s guards. Shops and restaurants owned by “Hu” people could be seen throughout Chang’an.

Foreign culture also made a great contribution to the cultural splendor of the Tang Dynasty, particularly within the performing arts. In the early Tang Dynasty, there were ten musical and dance programs, seven of which were from the Western Regions and abroad. The Hu Swirling Dance was the best known of all, and indispensable to any program of entertainment. The dance was performed, either as a solo or duet, on a small round carpet. The dancer or dancers swirled and spun dazzlingly, their dresses flying out in a manner that made them resemble a spinning top. Bai Juyi, a great poet of the Tang Dynasty, described the speed of this dance as faster than that of a spinning wheel.

In the early Tang Dynasty, the Chinese population was less than 18 million. A hundred years later, in 755, the population had reached 52.92 million. In ancient feudal society, the rate of population increase was an important indicator of the economic strength and social progress of a country. This 100-year period later became known as the Tang of Great Prosperity.