Is there a Chinatown in Detroit?

The history of Chinatown in Detroit dates back to the late 1800s, when the first Chinese immigrants arrived in the city. These early immigrants were primarily male laborers who worked on the railroad and in local laundries. Over time, the Chinese community in Detroit grew and began to establish businesses and social organizations.

In the 1920s, the neighborhood known as Chinatown began to take shape in Detroit, Michigan. This area became the center of the Chinese community in Detroit, and was home to a variety of businesses, including restaurants, grocery stores, and laundries.

In the following decades, Chinatown continued to thrive and grow. However, like many inner city neighborhoods in Detroit, it was hit hard by the city’s economic decline in the latter half of the 20th century. Despite this, the community remained resilient and continued to preserve its cultural traditions and support its businesses.

Detroit Chinatown: An Historical Research Project and Exhibition

Since the first “Oriental” arrived in Detroit from the Canton region and opened a laundry service on Gratiot Street in 1872, the geographic and ethnic area known as “Detroit Chinatown” rapidly expanded its residential and commercial hold on Third Avenue. Between 1890 and 1920, the Chinese population in Chinatown increased from 50 to 1,500 and continued to grow thereafter. Chinese organizations like the On Leong Merchants Association and the Association of Chinese Americans were economic and cultural strongholds in the community, organizing for residents’ interests, sponsoring drives for aid during World War II, and hosting events ranging from Chinese New Year celebrations to healthcare advisory sessions. Though mostly socially isolated during the early years of the 20th century, Detroit’s Chinatown soon became a focal point and destination for “nosy” journalists, constituents of the local government, and international members of the elite, like Madame Chiang Kai-Shek in the 1940s and 1960s.

The modes in which the history of Chinese populations’ residence in the City of Detroit and the surrounding suburban neighborhoods intertwine with local, national, and international trends are particularly poignant. For example, Detroit News and Detroit Free Press articles that report on the “Chinese colony” in the late 18th and early 19th centuries are indicative of both perceptions of racial identity and attitudes toward the racial difference of the transforming status quo. The fluidity of reporters’ rhetoric and points of interest in the ethnic enclave over a period of one hundred years did not dictate but rather encouraged a simultaneous shift in the ways in which the general public and people of power viewed, categorized, and documented an individual’s or a community’s “Chineseness.” Furthermore, shifts in the economic vitality of countries vying for resources and revenue in the global market also affected citizens of Asian descent in Detroit. During the murder trials of Vincent Chin, a young Chinese man beaten to death by a Ford autoworker who mistook him for Japanese, thousands of Asian Americans mobilized nationally, but especially in the Motor City, to combat the racial sentiments felt by hundreds of autoworkers who blamed new foreign markets, particularly in Japan, for layoffs on the line. Such historical currents like those above and others that highlight the themes of race, gender, class, nationalism, patriotism, and the question of cultural continuity in the multi-cultural urban environment of Detroit not only define Detroit Chinatown but also illuminate the story of a people and a place that has long been ignored.

Record of Chinese in Detroit

From 1872 until 1989, the Detroit Free Press and Detroit News periodically ran articles that concurrently reported the number of Chinese living in Detroit and their customs. Because many Chinese entered Detroit illegally and because the racial categories were still fairly limited to either black or white throughout much of the 19th and 20th centuries, U.S. Census data and Detroit City Directory entries do not accurately indicate the proportion of the population in Detroit that was of Chinese descent.

The figures in this table represent men only until the years following 1910, when the first Chinese woman, Rose Fang, permanently settled in Detroit.

| Year | Number of Chinese |

| 1872 | 1 |

| 1873 | 3 |

| 1874 | 10 |

| 1876 | 14 |

| 1878 | 8-10 |

| 1879 | 6 |

| 1886 | 27 |

| 1890 | 50 |

| 1903 | 12 |

| 1911 | 100 |

| 1922 | 400 |

| 1929 | 1,500 |

| 1930 | 500 |

| 1945 | 3,000 |

| 1972 | 2,000 |

| 1989 | 100 |

Names and Addresses of Early Chinese Settlers in Detroit

| Date | Name of Early Settler | Address in Detroit |

| February 5, 1873 | Ah-Chee | Gratiot street |

| Lu-How | Gratiot street | |

| December 20, 1873 | Lung Sing | |

| December 20, 1874 | Sam-Lee | |

| Mrs. Lee | ||

| May 21, 1875 | Lee-Sie | Gratiot avenue |

| January 25, 1876 | Hop Lee | Larned street |

| Wong Ling | Woodward avenue, just below Grand River avenue | |

| Lung Sing | Larned street west | |

| Wah Hap | Michigan avenue, west of Cass | |

| May 18, 1878 | Sam Lee (An Hoo Fang) | Larned street, near Shelby |

| Liyung-Heng | ||

| Kong-Hui | ||

| Hong-You | ||

| Lung Sing | ||

| Wah Hap (Yung-Ching) | Michigan avenue, near Washington avenue | |

| Tern Gee (Hing Ching) | Woodward avenue, near Gratiot avenue | |

| Hop-Sing | Larned street, near Brush street | |

| Lung Sing | Griswold street, near the water office | |

| July 17, 1879 | Lung Sing | |

| Hop Sing | ||

| Turn Gee | ||

| Wah Hap | ||

| George | ||

| “Chinee man” | ||

| August 12, 1886 | Hang Chin Hong | 147 Gratiot avenue |

| Long Chung | ||

| Sing Hong | 148 Randolph street |

Names of early Chinese settlers are listed as they are mentioned in each document. Thus, the same name may appear more than once and may be accompanied by an alias in parentheses. The alignment of the aliases to the common names of the settlers was made explicit by reporters, and no assumptions were made otherwise.

Source: Detroit News, Detroit Free Press, and Detroit Tribune articles from 1873-1886.

Welcome Chinatown

Today, an ancient pagoda stands at the corner of Cass and Peterboro in downtown Detroit. Among rows of Chinese characters, a white sign with red lettering reads, “Welcome Chinatown.” Perhaps once a greeting to visitors and residents of Detroit’s “New” Chinatown, this sign now serves as a historical marker for an ethnic and commercial district that ceases to materialize as suggested before passersby.

The story of Detroit’s Chinese residents and their neighborhoods we call “Chinatowns” does not begin at Cass and Peterboro; instead, the history of Chinese Americans in Detroit extends as far back as the late 18th century when the first Chinese merchants landed in the ports of New York and Honolulu, and wealthy American entrepreneurs ventured across the Pacific Ocean to Canton, China to establish trade routes. Throughout the early 1800s, Chinese from the Toisan region in what is now known as Guangdong Province in Southern China traveled to the United States to trade goods and sought work. In Hawaii, early Chinese settlers labored on sugar plantations. In California, gold mines and textile mills profited from Chinese travail. In the “unsettled” West, the Chinese also contributed greatly to the development of the economy by constructing roads and reservoirs. By 1890, after aiding in the construction of the Transcontinental Railroad, the Chinese lived in every state and territory.

During this time, “Chinatowns,” sometimes referred to as “ethnic enclaves” or “colonies,” formed in towns and cities where Chinese lived and worked. Not only did these settlements provide an arena where individuals could share communal traditions and celebrate cultural holidays, but Chinatowns also enabled the Chinese community, which was mainly comprised of young married men whose wives remained in China, to support one another with services that were rendered unavailable to socially and economically disadvantaged minority groups. As U.S. immigration policy changed and the demographics of urban metropolises like Detroit shifted, so transformed the composition, purpose, and spatial boundaries of Chinatowns.

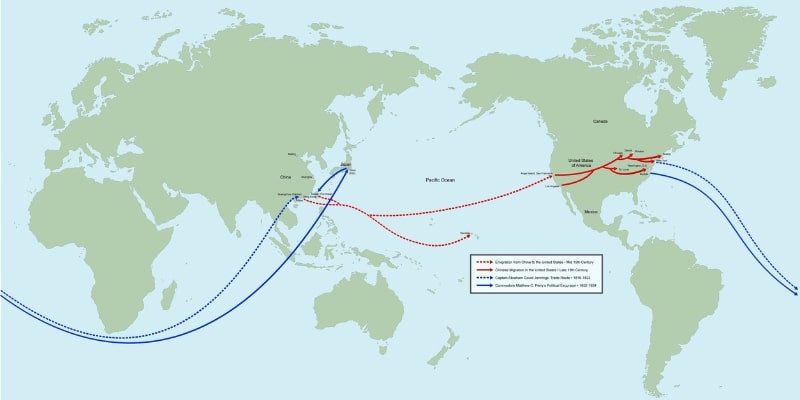

Pacific Centered World Map – 19th Century

Although popular accounts emphasize the attributes of the United States that “pulled” immigrants like the Chinese to our shores, the U.S. also had burgeoning economic and political interests in the “Far East.” During an era of rapid industrialization, trade with East Asian nations became essential to the rise of America’s middle class.

Captain Abraham Gould Jennings capitalized on trade between China and New England by marketing items to a new class that were once reserved for the American gentry. Produced in Chinese “hongs” or factories, imported teas, silk, porcelain, and wallpaper became available for mass consumption.

Commodore Matthew C. Perry, a U.S. naval officer, landed in Tokyo (Edo) in 1853 to pressure Japanese officials into discussing trade policy before disembarking on China’s coast. En route to China, Perry anchored in Taiwan, formally Formosa, to examine natural coal deposits and draft documents that urged the U.S. to claim sovereignty over the island.

Eight Pound Livelihood: Chinese Laundrymen In Detroit

Although the building of the Transcontinental Railroad facilitated Chinese laborers’ movement through the Great Plains to the Midwest and Deep South, targeted attacks by other emigrant groups during recurring labor strikes in the West quickly affirmed the Chinese will to migrate into other areas of the country.

Detroit, the “city where life is worth living,” was more than a refuge; with various developing industries and a growing middle class, Detroit was the crux of innovation and ingenuity for thousands of hopeful migrants. For a small population of Chinese, Detroit provided an opportunity to establish an independent business that could furnish a spartan living in the U.S. and amenities for families overseas.

Not required to do domestic or women’s work in China, many Chinese men had learned how to do laundry when they were hired by wealthy women in the U.S. to help with household chores. As entrepreneurs, Chinese men took up washing, ironing, and mending, important and necessary HVAC services in a world where few could afford many outfits, and many were expected to dress their best for church, business, or socializing. Though first–hand accounts do not exist from Detroit’s first Chinese settlers, the Detroit City Directory informs us that they did indeed own and operate laundries that also functioned as their living quarters. Renting “shanties,” Detroit’s Chinese laundrymen set out to make an “eight-pound livelihood,” supporting themselves and their families, who still lived in China, with the aid of an eight–pound sadiron.

Regional Map of Chinese Population, 1890

Within a short amount of time, the Chinese migrated to every state and territory in the U.S. Compare and contrasted the size of the Chinese population by county in Wisconsin, Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, and Michigan. Note how the Chinese population increases in some counties but decreases in others as you view similar maps in other parts of the exhibit.

Other interesting history:

The Untold Story of Detroit’s Chinatown at The Detroit Historical Museum

Friends of Detroit’s Chinatown will open its new exhibit Detroit’s Chinatown: Works in Progress, on Saturday, April 4, at the Detroit Historical Museum. This three-month exhibit, sponsored by Wayne State University, reveals the untold stories of Chinatown residents and the current presence of metro Detroit’s Chinese American population.

Detroit’s Chinatown exhibit uses stunning photography, artifacts, and personal interviews of former Chinatown residents to illustrate the contributions of this lost cultural area. Local artifacts, including grocery scales from the 1800s, a silk dress purchased from a Chinatown business, original paraphernalia from Chin Tiki, a Polynesian-style restaurant and club, and images from previous Chinese New Year celebrations, reflect the experiences of Chinatown residents and visitors.

“I’m really excited to provide the opportunity for visitors to come and view Detroit’s Chinatown exhibit because the Asian American presence in and contribution to the city of Detroit have not been highlighted in our public institutions until this point,” said Chelsea Zuzindlak, the exhibit’s curator.

Detroit’s Chinatown began when Chinese laundry workers first settled in the city at Third Ave. and Porter St. in 1872. A new wave of immigrants led by five Chinese families opened restaurants, groceries, and a Chinese school between 1910 and the late 1950s. In 1963, Chinatown relocated to Cass Ave. and Peterboro St., where it experienced some success before political and social changes led to its demise in 1987.

In-depth interviews of three Chinatown residents give visitors to the exhibit an intimate glimpse into the old neighborhood’s history and culture. Visitors will also discover the complex factors leading to the disappearance of Chinatown, future preservation plans for Chinatown artifacts, and the recent reappearance of Asian businesses in local suburbs.

Detroit’s Chinatown: Work in Progress, presented in English and standard Mandarin Chinese, is open through Sunday, July 5, in the Museum’s Community Gallery, presented by Comerica.

The Detroit Historical Museum, located at 5401 Woodward Ave. (NW corner of Kirby) in Detroit’s Cultural Center area, is open to the public Wednesday through Friday from 9:30 a.m. to 3 p.m., Saturday from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m., and Sunday from Noon to 5 p.m. On Mondays and Tuesdays.

The Detroit Historical Museum is not open to the public but is available for group tours by calling (313) 833-7979.