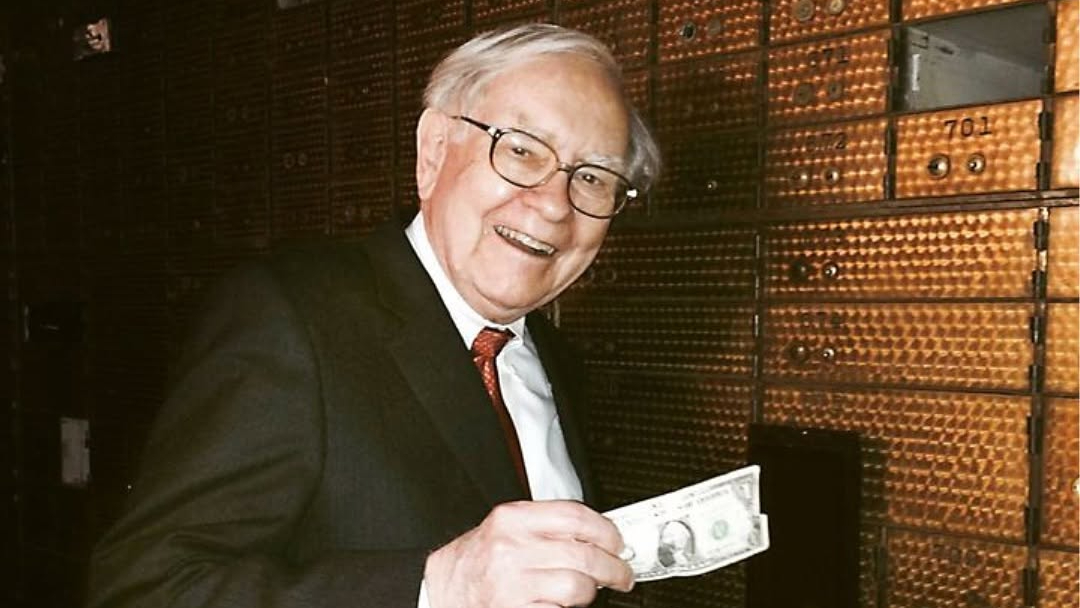

How Did Warren Buffett Make His First Million

Okay, so you've heard of Warren Buffett, right? The guy with the folksy charm, the cherry Coke addiction, and a bank account that could probably buy a small moon. We see him on the news, looking like he's about to tell you the secret to perfectly ripe avocados, and we think, "Man, how did that guy get so ridiculously rich?" Especially, you know, his first million. That’s like, the real mountain to climb. Before the billions, before the private jets (though he's famously not a fan of those), there was that magical, life-changing, “I can finally buy that really comfy armchair” million dollars. So, how did he do it? Let's break it down, because I bet you've had similar moments, even if your "million" was more like the "perfectly ripe avocado" of your dreams.

Imagine this: you're a kid, maybe you're nine or ten. What are you doing? Probably trying to trade your slightly squashed peanut butter sandwich for someone else's even more squashed cheese sandwich. Or maybe you're trying to convince your parents that that dusty old comic book is actually a collector's item. Well, young Warren wasn't just swapping snacks. He was already in the business of buying and selling. Think of it like this: you know how sometimes you get a bunch of birthday money and you’re tempted to blow it all on a giant bag of candy? Warren saw that money and thought, "Hmm, how can this candy money make more candy money?"

His first foray into "business" wasn't some elaborate scheme involving venture capitalists and PowerPoint presentations. Nope. It was much simpler, much more relatable. He started selling things. Things like Coca-Cola bottles. Now, this isn't like finding a forgotten ten-dollar bill in your winter coat. This was strategic. He'd buy a six-pack for, say, 25 cents, and then sell each individual bottle for a nickel. That's a 5-cent profit per bottle. Sounds small, right? It's like finding a penny on the sidewalk and thinking, "Score!" But imagine doing that with lots of pennies. It starts to add up, doesn't it?

Think about your own childhood ventures. Did you ever try to sell lemonade? Or maybe you were the neighborhood kid who’d mow lawns for a few bucks? That’s the spirit! Warren was doing that, but with a slightly more… deliberate approach. He wasn't just doing it for pocket money; he was doing it to reinvest. It’s like if you saved up your allowance and instead of buying that video game you wanted, you bought more ingredients to make more lemonade, so you could sell even more lemonade and eventually buy the video game and have some cash left over.

So, after mastering the art of the Coca-Cola flip, what was next? Well, he had a knack for spotting things that other people overlooked. He started buying used golf balls and reselling them. Why golf balls? Because golfers, bless their hearts, tend to lose them. A lot. It's like knowing that the lost-and-found bin at the mall always has a treasure trove of perfectly good scarves nobody claims. Warren was essentially saying, "Hey, instead of these things being lost forever, let's give them a second life, and make a little dough in the process." He’d find these stray balls, give them a quick clean, and then hawk them to golfers who were perfectly happy to snag a slightly used ball for cheaper than brand new.

This is where we start seeing the "Buffett Method" emerge, even if he didn't know it then. It’s about finding value where others don’t. It’s like when you’re at a garage sale, and everyone’s eyeing the fancy china, but you spot that perfectly functional, slightly dusty old toolbox that you know is worth way more than the $5 they’re asking. You’re not just buying a toolbox; you’re buying potential. Warren was buying potential in stray golf balls.

But it wasn't just about buying and selling physical goods. Oh no. Warren had a sharp mind for… well, for investing. Even as a teenager. He was fascinated by the stock market. Now, for most of us, the stock market is like trying to decipher ancient hieroglyphics while being chased by a flock of very angry pigeons. It seems complicated, intimidating, and frankly, a bit scary. But Warren saw it differently. He saw it as a way to make his money work for him, even when he was sleeping. It’s like having a tiny, diligent army of money-making elves that you can dispatch with a few keystrokes.

He started reading everything he could get his hands on about investing. Books, newspapers, anything that talked about companies and their performance. It was like cramming for the biggest test of your life, but the prize wasn't a passing grade; it was making your money multiply. He was learning to spot companies that were, in his words, like "a wonderful business at a fair price." Think of it like finding a restaurant that serves amazing food at a price that makes you feel like you're stealing.

His first actual stock market investment? It wasn't some flashy tech startup or a company that promised to make your hair grow back overnight. It was Cities Service Preferred Stock. He bought it when he was just 11 years old, with money he’d saved from his newspaper routes and, you guessed it, those bottle-selling ventures. He bought three shares at $38 each. Imagine being 11 and having $114 saved up. Most kids would be eyeing the latest video game console. Warren was eyeing the stock ticker.

And then, like any good investor (or anyone who’s ever bought something they immediately regretted), he saw the price of the stock go down. Ugh. That sinking feeling. It's like when you buy that impulse item at the checkout counter, and then five minutes later you're thinking, "What in the world was I thinking?" But Warren didn't panic. He held on. And then, things started to look up. The stock price climbed, and he eventually sold it for a profit. But here's the kicker, the part that really shows his budding genius: he sold it for $40 a share, making a nice little profit. But then, he realized he could have made even more if he'd held onto it longer. That was a lesson learned the hard way, the way most of us learn things, like not wearing white socks with black shoes (or is that just me?).

This experience taught him a crucial lesson about long-term investing. It wasn't about quick flips; it was about owning a piece of a good company and letting it grow. It’s like planting a tiny sapling and knowing that, with time and care, it will grow into a mighty oak tree. Most people want an instant fruit-bearing bush, but Warren was a patient gardener.

As he got older, his investments became more sophisticated, but the core principles remained the same. He’d look for companies with a strong competitive advantage, what he calls an "economic moat." Think of it like a castle. A castle with a really deep, wide moat is much harder for attackers to get into. Warren was looking for businesses that had something similar – something that made it tough for competitors to steal their customers or their profits. It’s like finding a bakery that makes the most delicious, unique pastries, and everyone in town goes there because no one else can make them quite the same way.

He also had a keen eye for undervalued companies. This is where the "fair price" comes in. He wasn't just buying any old company; he was buying companies that he believed were worth more than their current stock price. It’s like finding a diamond in the rough at a pawn shop. Everyone else sees a dusty old trinket, but you see the hidden sparkle, the underlying value. He'd find companies that were temporarily struggling, or that the market had unfairly overlooked, and he’d buy them up, knowing that their true worth would eventually be recognized.

One of his earliest major successes that truly set him on the path to that first million (and beyond) was his involvement with a struggling textile mill called Berkshire Hathaway. Now, this wasn't a glamorous business. Textile mills, back then, were sort of like dial-up internet today – a bit outdated and on their way out. But Warren saw something in it. He started buying shares, and eventually, the company became his investment vehicle. He didn’t try to fix the failing textile business itself; instead, he started using the cash flow from the mill to buy other, more profitable businesses.

It’s like inheriting a slightly leaky but structurally sound old house. Instead of trying to patch every single leak (which is exhausting!), you start using the rent from that house to buy a brand new, state-of-the-art apartment complex. You’re using the old to fund the new and the better. Berkshire Hathaway became that engine, that money-making machine, fueled by a series of smart acquisitions of businesses that were actually doing well. He’d buy insurance companies, companies that made ice cream, companies that made anything and everything, as long as they were good businesses.

So, to recap the journey to that first million: it wasn't a lottery win or a sudden windfall. It was a combination of entrepreneurship (selling Cokes, golf balls), prudent saving (reinvesting profits), early education (devouring books on investing), patient long-term investing (holding onto good companies), and a knack for spotting undervalued assets (buying into businesses with hidden potential). It was about making smart decisions, even when he was just a kid, and learning from his mistakes along the way. It's the same principle as learning to ride a bike – you wobble, you fall, you scrape your knee, but eventually, you’re cruising down the street, wind in your hair, feeling pretty darn good about yourself. Warren Buffett just happened to be cruising towards a much, much bigger bank account.

And that, my friends, is how a kid who started by flipping six-packs of soda eventually amassed a fortune. It’s a story that’s both inspiring and, dare I say, a little bit like your own journey of trying to make your paychecks stretch a little further, or that time you scored a sweet deal on something you really wanted. It's proof that with a little bit of brains, a lot of patience, and maybe a healthy dose of folksy wisdom, that first million isn't just a pipe dream. It's a possibility, one smart decision at a time.